Radar sensors are often intuitively compared with optical systems. Cameras produce images that humans have learned to interpret from early childhood: two-dimensional representations of visible surfaces with colors, textures and shapes. Radar however, is based on fundamentally different physical principles. This difference frequently leads to misunderstandings about what kind of information a radar provides and how its output should look.

This article explains the fundamental differences between radar and camera sensing, and why radar representations should not be interpreted like camera images.

Radar does not generate images in the optical sense. Instead, it measures physical properties of reflected electromagnetic waves and represents these measurements in an abstract form. To interpret radar data correctly, it is essential to understand what radar actually measures—and what it does not.

What does “seeing” mean in radar?

Radar measures neither brightness nor color. It evaluates reflected radio-frequency signals and derives physical quantities such as:

- Distance, derived from signal propagation time or beat frequency

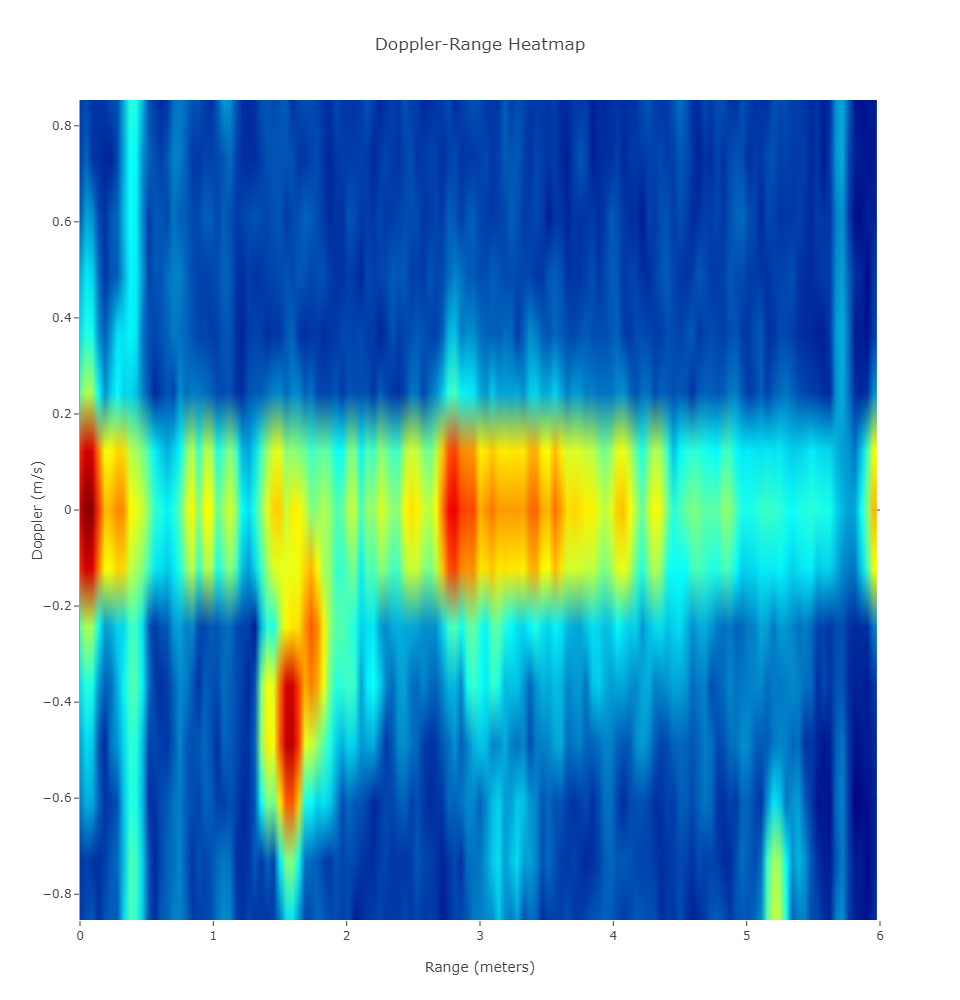

- Relative velocity, derived from the Doppler frequency shift

- Direction, derived from phase differences between multiple antennas

- Signal strength, representing the amount of reflected energy

The received signals initially exist in the time or frequency domain. Only through signal-processing steps — such as FFTs, filtering and detection — do representations like range profiles, heatmaps or point clouds emerge. These representations are visualizations of measured data, not images of object surfaces.

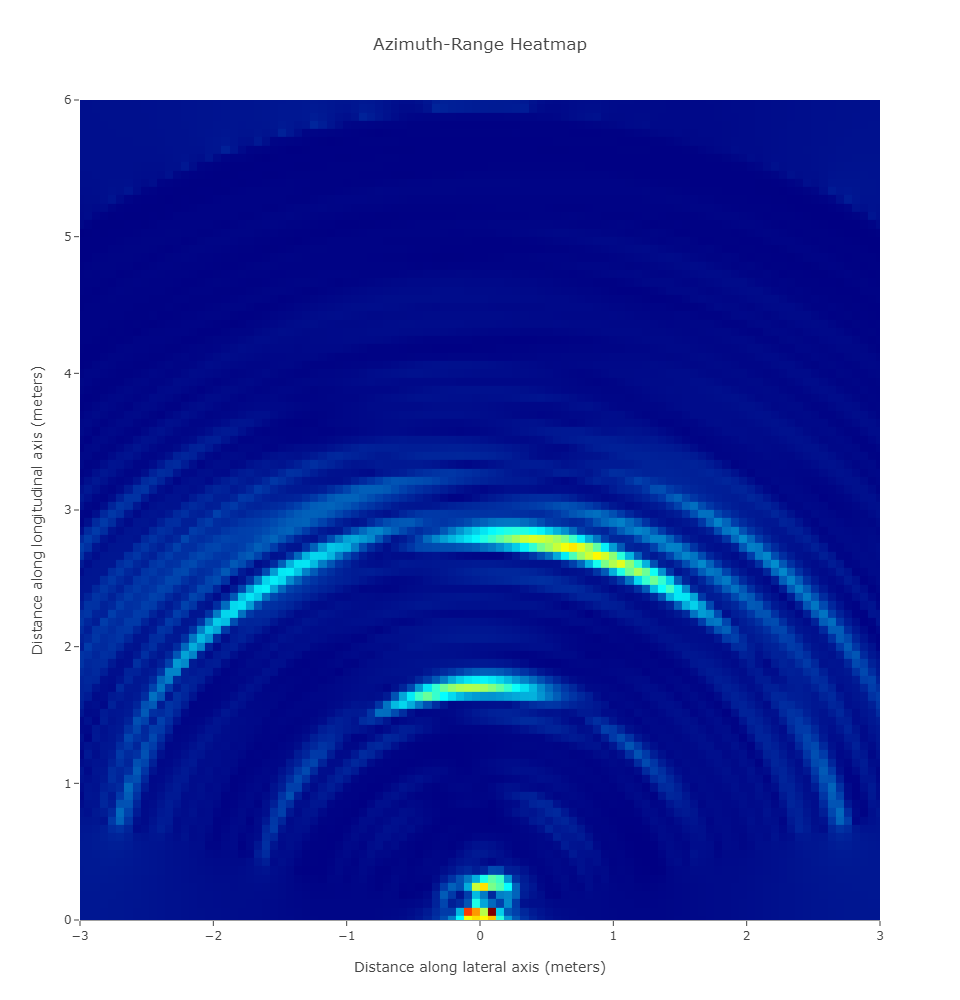

In modern FMCW radar systems, these quantities are not measured independently. They form a multi-dimensional measurement space, often referred to as a radar cube, spanning range, velocity and angle. Each cell in this cube represents measured signal energy for a specific combination of these dimensions. Many common radar visualizations, such as range–Doppler or range–angle maps, are two-dimensional slices or projections of this higher-dimensional measurement space.

This difference becomes particularly clear when comparing an optical image with a radar measurement space: while the camera shows surfaces in a two-dimensional image, radar data exists as a multi-dimensional volume that must be interpreted through projections and processing.

The camera shows visible surfaces in a two-dimensional image, while the radar representation illustrates signal energy distributed across range, velocity and angle. Radar data represents measurement domains rather than object appearance.

Why radar does not “see” like a camera

The key difference between radar and camera sensing is not resolution or coordinate system, but the physical interaction with the environment.

Radar does not capture surfaces

Cameras capture reflected light from object surfaces. Each pixel corresponds to a surface element in a specific direction. If a surface is visible and illuminated, it appears in the image.

Radar, by contrast, primarily responds to electromagnetic scattering. It does not sample surfaces continuously. Instead, the received signal is dominated by a limited number of strong scattering mechanisms. In practice, significant radar reflections typically originate from:

- Edges and corners (geometric discontinuities)

- Metallic or conductive structures

- Abrupt changes in material or geometry

- Specular reflections, depending on object orientation

This leads to several effects that are frequently misunderstood:

Large objects may appear as only a few reflections

Even when an object is fully within the radar’s field of view, the measured signal energy may be dominated by only a small number of scattering centers. Large portions of the object can contribute little or no radar return.

Absence of reflections does not imply absence of an object

Large, smooth or homogeneous surfaces can reflect energy away from the sensor. Depending on orientation and material, such surfaces may produce weak, unstable, or no measurable radar response, despite being physically present.

Object orientation strongly influences the radar response

Small changes in viewing angle can significantly alter which scattering mechanisms dominate. As a result, the radar appearance of an object can change even if the object itself remains stationary.

Radar measures interaction, not appearance

Signal strength represents how strongly parts of the scene scatter electromagnetic energy back to the sensor. It does not directly correspond to object size, shape or visual prominence.

Radar therefore does not describe surfaces, but rather dominant scattering centers, whose visibility depends on geometry, material and viewpoint.

Phase and multipath effects

Radar signals carry phase information. Small changes in position or orientation can lead to constructive or destructive interference, causing reflections to appear, disappear or change significantly in amplitude.

In addition, radar waves often reach the receiver via multiple paths due to reflections from the ground or surrounding structures. These multipath effects can create additional responses that do not correspond to a direct line-of-sight reflection.

What may appear as artifacts from an optical perspective are expected physical effects in radar sensing.

Radar representations are not images

Radar heatmaps and point clouds should not be interpreted like pixel-based images. Each displayed point or color value represents a measurement cell in distance, velocity or angle.

These measurement cells:

- have a finite spatial extent

- may contain energy from multiple physical locations

- are the result of a signal-processing chain

Radar representations are therefore interpretations of measured data, not direct depictions of reality.

How radar data should be interpreted

Radar answers different questions than a camera. Typical questions addressed by radar are:

- Is there an object at a certain distance?

- Is it moving, and at what speed?

- How stable is a reflection over time?

Radar excels at measuring distance, motion and dynamics, independent of lighting conditions or visibility. Expecting radar output to resemble camera images often leads to misinterpretation.

Camera vs. Radar – Key differences at a glance

| Aspect | Camera | Radar |

|---|---|---|

| What is measured | Light intensity and color | Distance, relative velocity and angle |

| What appears in the data | Object surfaces | Dominant scattering centers |

| Spatial representation | Two-dimensional image | Measurement space (range, velocity, angle) |

| Motion information | Estimated over time | Measured directly via Doppler |

| Typical challenges | Low light, glare, fog | Multipath, orientation-dependent reflections |

Conclusion

Radar does not attempt to replicate optical vision. It measures distance, motion, direction and scattering strength through electromagnetic interaction and represents these measurements in abstract domains.

The fact that radar representations do not look like camera images is not a drawback—it is a direct consequence of the different physical information radar provides.

Understanding what radar measures and how these measurements are represented is the key to using radar effectively.

Radar does not show what objects look like. It shows where they are and how they move.